Ruwanthi Abeyakoon

The historical connections between slavery and Britain’s imperial past have come under much scrutiny in recent years.

Recently a UN judge announced that UK is likely to owe more than £18,8tn in reparations for its historic role in transatlantic slavery which sparked a nationwide debate. A report co-authored by the judge, Patrick Robinson who has been a member of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) since 2015 and has been researching reparations as part of his honorary presidency of the American Society of International Law, says the UK should pay $24tn (£18.8tn) for its slavery involvement in 14 countries. Despite being a major driving force behind the Atlantic slave trade, English lawmakers never approved legislation legalizing slavery. In the well-known 1772 Somerset case, Lord Mansfield decided that as slavery was illegal in England, James Somerset, an escaped slave who had been transported to England, could not be forced to be sold in Jamaica. Somerset was freed as a result.

Robinson assembled the Brattle Group Report on Reparations for Transatlantic Chattel Slavery, which included economists, attorneys, and historians.

The study, which was published in June of this year, is regarded as one of the most thorough attempts to date to measure the damages brought about by slavery and determine the amount of reparations that each nation is obligated to pay. According to the research, 31 former slave-holding nations, including Spain, the US, and France, must pay a total of $107.8 trillion (£87.1 trillion) in reparations.

The assessment of the five negative effects of slavery as well as the wealth acquired by the participating nations served as the foundation for the assessment. The paper lays out payment schedules spanning several decades, but it leaves it up to governments to agree on the amounts and methods of payment.

Reflecting on transatlantic slave trade

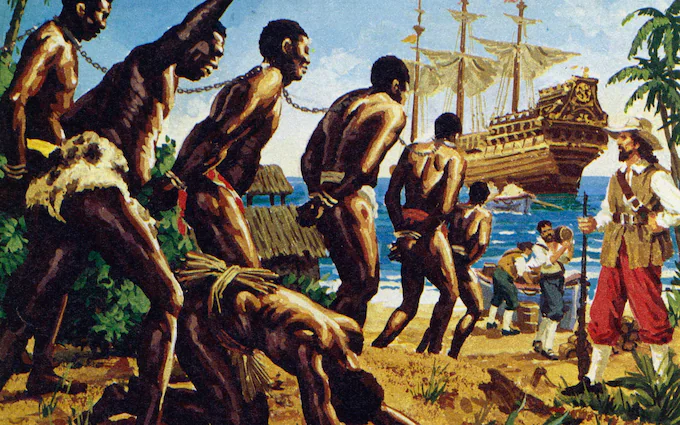

Millions of Africans were forcibly removed from their homes, transported over the Atlantic Ocean, and sold into slavery in the Americas during the horrific and dehumanizing transatlantic slave trade, which lasted for several centuries.

The transatlantic slave trade peaked in the 18th century and lasted three centuries in Britain. Acts of Parliament that ended the trade in 1807 and outlawed slavery in the colonies starting in 1833 were the result of African slave rebellions and resistance, as well as the British abolition movement.

In 1562, Britain became involved in the transatlantic slave trade, and by the 1730s, it was the largest slave-trading nation in the world. It was quite profitable to travel the triangle route, which connected Europe to Africa, the Americas, and back to Europe. With Glasgow and Lancaster providing support, ships from Liverpool, London, and Bristol dominated the slave routes, with London serving as the system’s financial hub.

During the first leg, items from ships departing from Britain were traded for enslaved Africans along the coast of west Africa. After that, these individuals were shipped across the Atlantic to be bought as slaves and forced to labor on plantations. More than three million Africans were carried by British ships, mostly to its colonies in the Caribbean and North America.

Subsequently, the identical vessels made their way back to Britain with “slave grown” goods, such as cotton, sugar, and tobacco. In Britain, these goods were consumed in enormous quantities. Many facets of British society and the country’s economy gained from the slave trade, including enterprises, labor unions, and consumers in addition to the landowners, financiers, and merchants who controlled and oversaw the trade. Tens of thousands of sailors, armies of British laborers, and thousands of slave ships were all part of the trade.

Benefits of transatlantic slave trade were all over. Everything from the bustling slave ports to the opulent mansions of the affluent, the jobs generated in industrial cities, and the coffee and tobacco stores scattered across British cities. Initially, few voiced ethical or theological concerns regarding the slave trade and slavery.

Parliament and the slave trade

For many years, Parliament had allowed a sizable and expanding African enslaved population in the British colonies, with the encouragement and assistance of the royal family. Plantation owners, investors, and dealers made enormous profits from the slave trade.

More than a hundred acts supporting and defending the slave trade were passed by Parliament. A large number of politicians and other businesspeople held stakes in the plantations, slave trade firms, and goods made by slaves, like sugar and cotton. The slave trade continued to increase Britain’s prosperity because of these exotic items and the riches they produced, which proved to be alluring.

For instance, William Ewart Gladstone who served as Prime Minister four separate times between 1868 and 1894 and his family made its vast wealth through the sugar trade, with his father, John Gladstone, owning many slaves and several plantations in the West Indies. John Gladstone and William’s brothers made compensation claims following the 1833 Slavery Abolition Act and John received the largest payout of more than £100,000, which is £12 million in today’s money. Although William Gladstone did not own slaves personally, he benefited hugely from his family’s wealth. It supported his parliamentary career, and he inherited a fortune when his father died.

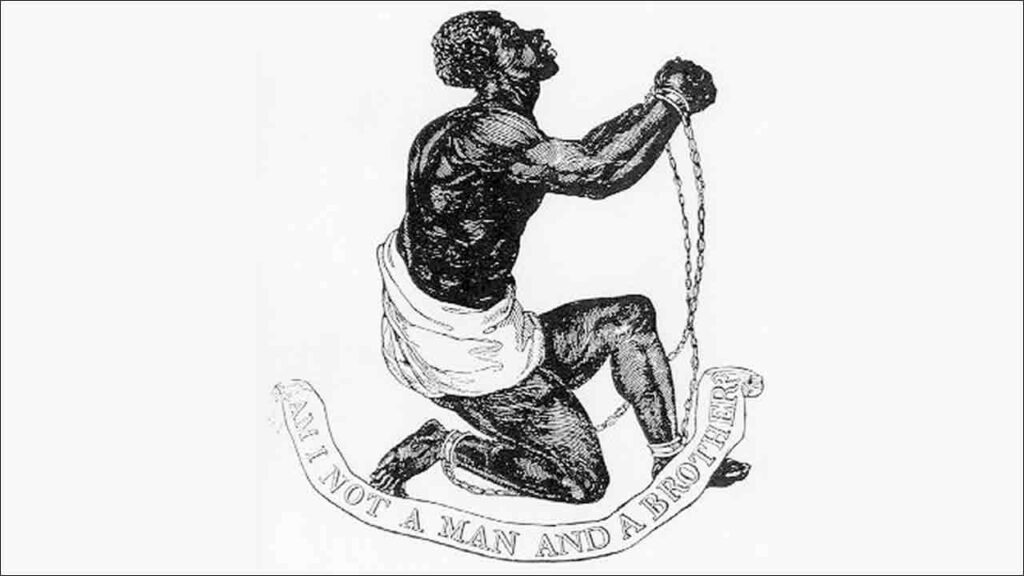

The Abolition Movement

Public perceptions of slavery started to shift by the late 1700s. Enslaved peoples’ acts of revolt in the colonies were growing, while opposition to slavery was becoming more vocal in Britain. However, ending the slave trade was not an easy task. Slavery had been a part of British society and commerce for centuries.

Following the American War (1776–1783) and the establishment of a black refugee community in London, abolition at last gained significant political attention. The Quakers were the first Christian sect to forbid the ownership of slaves, making them the first to oppose slavery. In 1783, they presented the first anti-slavery petition to Parliament and organized political parties and petitions.

As abolitionists shared their experiences and made the general public aware of the reality of slavery, the cause grew stronger. Large numbers of men and women signed hundreds of petitions calling for the trade to be outlawed, and lawmakers at Westminster started debating the issue and promoting reform and the abolition of slavery.

Olaudah Equiano

Olaudah Equiano (c. 1745–1797) emerged as one of the most well-known and significant African American voices in the British abolitionist movement in the late eighteenth century. His autobiography, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, was published in 1789 and detailed his experiences being a slave and being free. The public’s perceptions of slavery and the slave trade were influenced by the book. Equiano wrote: “The abolition of slavery would be in reality an universal good. Tortures, murder, and every other imaginable barbarity and iniquity, are practiced upon the poor slaves with impunity. I hope the slave-trade will be abolished. I pray it may be an event at hand.”

Equiano addressed the government directly on the issue of slavery and the abolition of the slave trade in published letters and participated in House of Commons debates on the topic in 1788. He wrote to lawmakers, and in 1789, one of his letters to Lord Hawkesbury was produced as evidence before a parliamentary committee.In order to promote his book and the abolitionist cause, he traveled the nation.

Other well-known opponents of slavery were former slaves who lived in Britain, Ottobah Cugoano (c. 1757–1791) and Mary Prince (1788–1833). Similar to Equiano, they wrote autobiographies detailing the horrors of slavery and were outspoken opponents of slavery.

Abolition of the Slave Trade Act, 1807

In 1805 an abolition bill failed in Parliament, for the 11th time in 15 years. Abolitionists inside Parliament, led by MP William Wilberforce, and outside Parliament including Britain’s black community, quickly focused on their next effort – the Foreign Slave Trade Abolition Bill of 1806. This would prevent the import of slaves by British traders into territories belonging to foreign powers. When the Bill passed in May 1806, the stage was set for full abolition of the British slave trade.

In 1807 Prime Minister Lord William Wyndham Grenville, introduced the Slave Trade Abolition Bill. Although it was met with resistance from the Duke of Clarence (the future king William IV) and other peers with West Indian interests, the House of Commons voted in favour of the bill by 283 votes to 16 – a victory that passed all expectations.

Unyielding battle

Slavery continued even after the Act of 1807, which was a significant win for the abolitionist movement. It did not, however, cease the ongoing enslavement of those who had already been taken to the colonies, even though it had stopped the legal traffic in slaves. In addition, there was an unauthorized transatlantic slave trade, and after 1807, over a million Africans were sent to the Americas, primarily to Brazil and Cuba.

Slavery Abolition Act, 1833

The goal of the abolitionists was to end slavery entirely inside the British Empire, and they persisted in their struggle. Parliament approved the Slavery Abolition Act in 1833. It stipulated that on August 1, 1834, all slaves in British dominions—apart from the countries of the East India Company—would be set free.

Even while this win had political significance, the act’s provisions weren’t favorable. It had provisions requiring slave owners to receive £20 million in compensation and for freed slaves to participate in “apprenticeship” programs until 1840. Members of parliament and their families were among the beneficiaries of the compensation plan.

Architects of Resolve

In the late 1700s, the parliamentary anti-slavery campaign was led by William Wilberforce (1759-1833), MP for Hull. From 1791, Wilberforce brought annual abolition motions to the House of Commons, but each was defeated. After 18 years of campaigning for abolition, Wilberforce received a standing ovation during the key Commons debate on the 1807 Abolition of the Slave Trade bill.

Thomas Fowell Buxton Hansard is another prominent figure of this time who supported the compensation and apprenticeship schemes. He believed that they were necessary means to achieve abolition, but he was strongly criticized by other abolitionists. Following abolition, Buxton joined the push to abolish the apprenticeship program and persisted in advocating for additional measures to protect the rights of emancipated slaves. After losing his seat in 1837, he kept up his campaign, and in 1838 he witnessed the final repeal of the scheme from the Strangers Gallery in the House of Commons.

Stephen Lushington was an MP between 1806-8 and 1820-41. Like a lot of other MPs, Lushington came from a family of slave owners. Nonetheless, he actively backed Wilberforce and was dedicated to ending the slave trade and slavery. During the 1807 Abolition of the Slave Trade Bill discussion in Parliament, he spoke in favor of the bill.

One of the founding 12 members of the significant London Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade in 1787 was the ardent abolitionist Thomas Clarkson. In addition to gathering information for Parliament, Clarkson was in charge of abolitionist campaign promotion on a national level.

Local Quaker groups helped him as he traveled to all major ports in Britain as part of his abolition campaign. Wilberforce’s later activity in the House of Commons benefited greatly from his research.

International Day for the Remembrance of the Slave Trade and its Abolition

The rebellion that would be instrumental in ending the transatlantic slave trade started on the evening of August 22 to 23, 1791, in Saint Domingue, which is now part of the Republic of Haiti.

The International Day for the Remembrance of the Slave Trade and its Abolition is observed on August 23, every year, in light of this. Many nations first observed it, most notably Haiti (August 23, 1998) and Gorée Island, Senegal (August 23, 1999).

All peoples have a responsibility to remember the horror of the slave trade on this International Day. The event should provide a forum for a group discussion of the historical reasons, the strategies, and the outcomes of this tragedy, as well as an examination of the relationships that have resulted from it between Africa, Europe, the Americas, and the Caribbean, in line with the objectives of the intercultural project “The Routes of Enslaved Peoples”.

Government responses to reparations

Although the Brattle Report has sparked interest in the reparations movement, it is very improbable that the countries involved will follow its recommendations. Caribbean countries have sought slavery reparations from these governments for years with limited success.

Demands for an apology and compensation from the UK government for its involvement in slavery were rejected by Prime Minister Rishi Sunak. Millions of Africans were coerced into slavery and forced labor, particularly on plantations in the Caribbean, between the 16th and 19th centuries, thanks to the participation of British authorities and the monarchy in the trade.

Britain also played a significant part in putting a stop to the trade by enacting a legislation outlawing slavery in 1833 through Parliament. There has never been an official apology or offer of compensation from the British government for slavery.

Legal arguments

As to how reparations could be achieved, UN Judge Robinson said that was up the governments to decide. “I believe a diplomatic solution recommends itself,” he said. “I don’t rule out a court approach as well.” There is intense debate on the legality of official requests for reparations.

Though no concrete steps have been taken, representatives of Caribbean states have previously declared their desire to take the matter before the ICJ. Reparations can take many different forms, but they are generally understood to be compensation for anything that was judged unfair or incorrect.

Leaders, activists, and descendants of slave owners from the Caribbean have been applying growing pressure on the Western government to get involved in the reparations campaign in recent years.

A few descendants of slave owners have tried to alter their ways, including the family of 19th-century Prime Minister William Gladstone and former BBC journalist Laura Trevelyan.

Regarding current slavery-related issues, modern slavery and human trafficking still exist in many regions of the world. These problems include human trafficking, exploitation, and forced labor, occasionally on international scales. Human rights activism, legislative frameworks, and international cooperation are all part of the fight against modern slavery. It will need ongoing awareness-raising, education, and teamwork to end contemporary forms of exploitation and create a fairer and just global society.