By Henry Tillman

The UK has been investing in Malaysia for the past 60 years, in fact, it was the leading FDI investor in Malaysia for its initial several years after independence. However, by the mid-1980s, for numerous reasons, the UK was overtaken by Japan (focused on the electronics industry) and Singapore (increasing trade linkages) in FDI investment. These FDI trends have accelerated in today’s rapidly evolving multi-polar greening world, led by technology and digitization.

Within the past decade, not only has UK interest in FDI in Malaysia declined, three of the UK’s largest companies have made significant exits. Conversely, Malaysia has become an increasingly active investor in the UK over the past decade and is currently leading two of the UK’s leading infrastructure projects. In spite of these developments, both countries house large, international businesses which combined with their financial markets can assist both countries in developing future growth.

Inbound Investment into Malaysia

In our November issue of Asia Investment Research; Malaysia’s Economic Transition: from Plantations and Palm Oil to tech and Green Energy (complimentary download here) we

examined inbound investment into Malaysia by components:

- Semi-conductors – $10 billion, USA (Intel) and EU (Infineon, Nexperia, Austria Technologie)

- Algae to energy – 35 Japanese companies (including Honda, Mitsui Chemicals, and ENEOS)

- NEV (batteries) – Samsung (Korea), $1.3 billion

- 5G – Ericsson (Sweden)

- Data centres – USA (Microsoft, Google, AWS)

- Cloud computing – USA (Google)

- Methanol – EU (Air Liquide) and Korea (Samsung)

- Biodiesel/biofuels – China (Shaanxi Construction)

- Regional logistics – China (Alibaba)

- Biodegradable packaging – UAE

Inbound M&A/Investments into Malaysia

Malaysian M&A markets showed declines during 2019 and 2020 and were primarily focused on domestic consolidation. M&A volumes and aggregate amount rapidly returned in 2021. Specific industries seeing inbound M&A and PE (by country).

- China – hydrogen, engineering, green energy

- Singapore – tech, e-commerce, healthcare

- USA – financials (2), healthcare, insurance

- Taiwan – consumer, tech

- Korea – tech (2), fintech/eWallet

- Italy – insurance

- India – fintech

- UAE – infrastructure

What is clear from the data above is the absence of UK names from these lists. While there were some UK companies investing capital. AstraZeneca $125+ million in 2019, Smith & Nephew $100+million in 2022, GKN $35 million also in 2022, Owen Mumford (ND in 2017), and a major asset swap (Shell 2022) most were existing office extensions such as Arup (300 employees), Ideagen (UK parent sold in July), audit part Inc (less than 50 employees in Malaysia), Mitra Innovation (recently opened an office in Singapore) and Sage, which opened in Malaysia some 30 years ago. BAE Systems did make a number of capital investments in Malaysia, but these seemed to end in 2015.

Instead, the UK trend relative to investments over the past few years was actually to exit and withdraw capital from Malaysia. In 2020, Tesco sold its Thailand and Malaysian businesses (Malaysian was less than 50%) for $10.8 billion. Also in 2020, BP sold its petrochemicals business for $5 billion. This business had several manufacturing facilities in Asia including China, Korea, Taiwan, and Malaysia. In 2021, Dyson exited its corporate partnership in Malaysia, relocating manufacturing to Singapore (these exits also were apparent in other ASEAN countries).

Malaysia into the UK

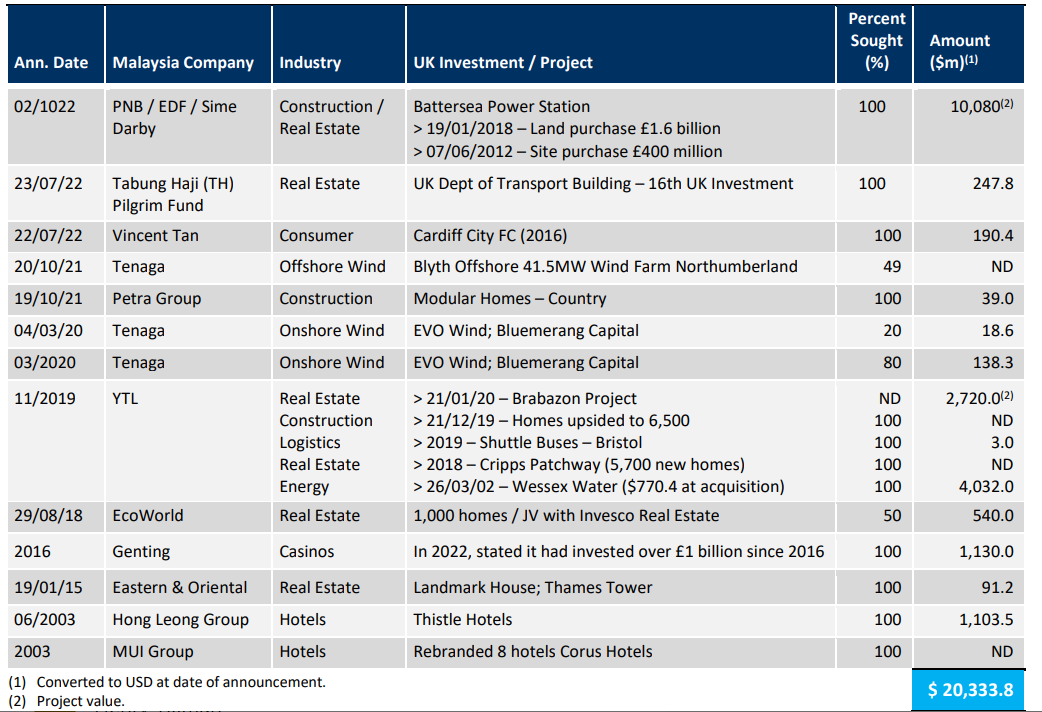

While the UK was reducing its overall capital exposure to Malaysia, Malaysia has grown its investments in the UK substantially and consistently, especially over the past decade, as shown in the table below.

Historically, the majority of Malaysian investment into the UK over the past two decades has been led by the real estate and construction segments. These have been followed by hotels, consumers, and gaming. Over the past five years, Malaysia has been increasingly investing in UK renewables, led by YTL in Bristol (owner of GENeco waste to energy).

It is the two major infrastructure investments that comprise most of the investment. YTL has been investing in the Bristol area for the past decade. In 2020, the Bristol City Council approved plans for the new YTL Arena Bristol Complex which will see three former aircraft hangers (former home to Concorde) transformed into an entertainment venue, with a 17,080-person capacity arena (3rd largest in the UK). However, the largest investment by far is the renovation of the Battersea Power Station. Some 40 years ago, it was supplying a fifth of London’s electricity. After decades of sitting derelict, it is back and set to become one of London’s top retail and leisure destinations. The King of Malaysia attended the re-opening in October.

While the actual investment numbers do show a sizeable investment gap between the two countries has emerged over the past decade, as 2022 ended we set out two examples of how these two markets/countries, linked for the past 60+ years, remain complementary as evidenced below:

- UK-based Shell announced two transactions involving some of their multiple Malaysian energy assets. In December, Shell agreed to sell its equity stake in two offshore, non-operational production-sharing contracts (they own 19 in Malaysia) to Petroleum Sarawak Exploration & Production for $475 million. Only two months prior, Petronas, 80% owner of these assets, and Shell agreed to develop the Rosmari-Marjoram gas project, situated 220 km off the coast of Bintulu, Sarawak, Malaysia to be powered by renewable energy, using solar power.

- In November, Kuala Lumpur Kepong (KLK) was reportedly examining options to increase its circa 25% stake in UK-based and listed Synthomer plc. KLK, already Synthomer’s largest shareholder, is doing so following Synthomer’s drastic 2022 share price decline, its high leverage ratio, and a substantial downturn in its UK rubber glove business. This comes at a time KLK itself is also examining strategic options, one of which could be a separately listed downstream unit, which is currently vertically integrated under the KLK corporate structure. We suspect that both the LSE and Bursa Malaysia would ultimately welcome such a listing.

Finally, it is important to note that the historical relationship both countries have shared in healthcare remains intact today. While healthcare has not attracted major capital investment over the recent past, both countries played integral roles in the COVID pandemic, the UK with vaccines, and Malaysia with PPE. There are joint educational programs to continue this collaboration in the future.

Trade Conclusion

By Chris Devonshire-Ellis

While the ability of the UK to attract Malaysian investment will have been welcomed, there are warnings signs that UK businesses are not being encouraged enough to invest in ASEAN member states. Malaysia is an Asian Tiger: it has a population of 33 million, attained a GDP (PPP) of US$373 billion in 2021, and has a projected 2023 GDP growth rate of 4.2%. That said, GDP growth during Q3 2022 achieved 14.2%, suggesting that a global slowdown will affect Malaysia. If the country’s 2023 economic planning is on the money, growth could be rather higher. This compares with predictions for the UK economy to contract during 2023 by about 1.3%.

The primary lesson to be learned here is that the UK needs to be better prepared to incentivize its businesses to invest in growth markets. Malaysia is one of these, as is the entire ASEAN bloc, of which Malaysia is one member of ten countries also including Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam. This ought to fit in with London’s current political stance in hedging against China, where political opposition has meant many UK businesses have felt headwinds against investing in the country. Although we take the opposing view as China recovers from Covid and has put in place numerous incentives to attract investment into supplying a middle-class population set to reach 900 million within a decade.

But be that as it may – ASEAN is also experiencing a large growth in demand. ASEAN members such as Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam, (click on the links for more information) have all been opening up their markets to foreign investment. All recorded growth rates averaging 6.2% in 2022, while the overall ASEAN economy is set to reach US$5.2 trillion by 2025.

To compare, the total trade in goods and services between the UK and ASEAN Member States was £36.2 billion in the four quarters to the end of Q3 2021, suggesting that the UK has not been concentrating business and trade minds enough on this market. That the UK’s investment figures into Malaysia have retrenched suggests this is the case, an issue reflected by the position the UK holds within the ASEAN secretariat – the UK only has the status of a dialogue partner.

Within the main ASEAN economies, trade ties are also at a relatively low level as opposed to specific trade agreements. With Indonesia, a trillion-dollar economy in its own right, the UK has a “Joint Economic Trade Committee” (JETCO) to ‘discuss’ trade. With Malaysia, the UK has the same, as it does with Thailand. The Philippines has a Developing Countries Trading Scheme (DCTS) with the UK, while there are free trade agreements with Singapore and Vietnam.

The two FTA aside, the other agreements are discussion-led groups ‘at the Ministerial level’ and have been largely held online. We suspect that the contents of these meetings do not by and large involve the wider business and trade community. This has resulted in ASEAN nations – showing some of the fastest growing global growth trajectories and with significant consumer population growth rates, being fairly low down in the pecking order of UK trade partnership volumes.

| ASEAN member | UK trade partner status by volume |

| Indonesia | 54th |

| Malaysia | 41st |

| Philippines | 65th |

| Singapore | 20th |

| Thailand | 43rd |

| Vietnam | 39th |

Taken as an average, this would equate the current trade importance of the primary ASEAN nations with the UK at a ranking of about 43.6, which equates to levels akin to countries such as Cyprus or Morocco. Clearly – much more needs to be done to engage. The disappointing UK-Malaysia trade and investment figures appear to bear this out. The benefits of doing so are there for the UK-based manufacturing entrepreneur:

- ASEAN-based businesses enjoy free trade amongst other ASEAN states;

- ASEAN has additional free trade agreements with China and India. Assuming rules of origin criteria are met, UK-owned businesses in ASEAN can take advantage of these agreements;

- ASEAN members are part of the RCEP free trade agreement, which also includes Australia, Japan, New Zealand, and South Korea;

- ASEAN members Brunei, Malaysia, Singapore, and Vietnam are also members of the CPTPP trade agreement, which also includes Canada, Chile, Japan, Mexico, and Peru.

British businesses interested in establishing operations in Malaysia and ASEAN may contact Dezan Shira & Associates at asia@dezshira.com or visit www.dezshira.com. Our 2023 Guide To Doing Business in ASEAN can be downloaded here.